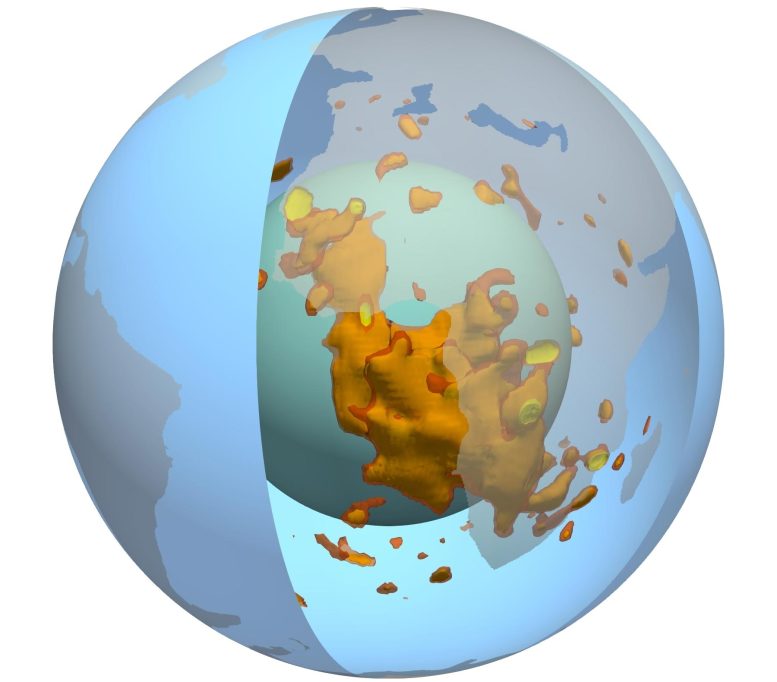

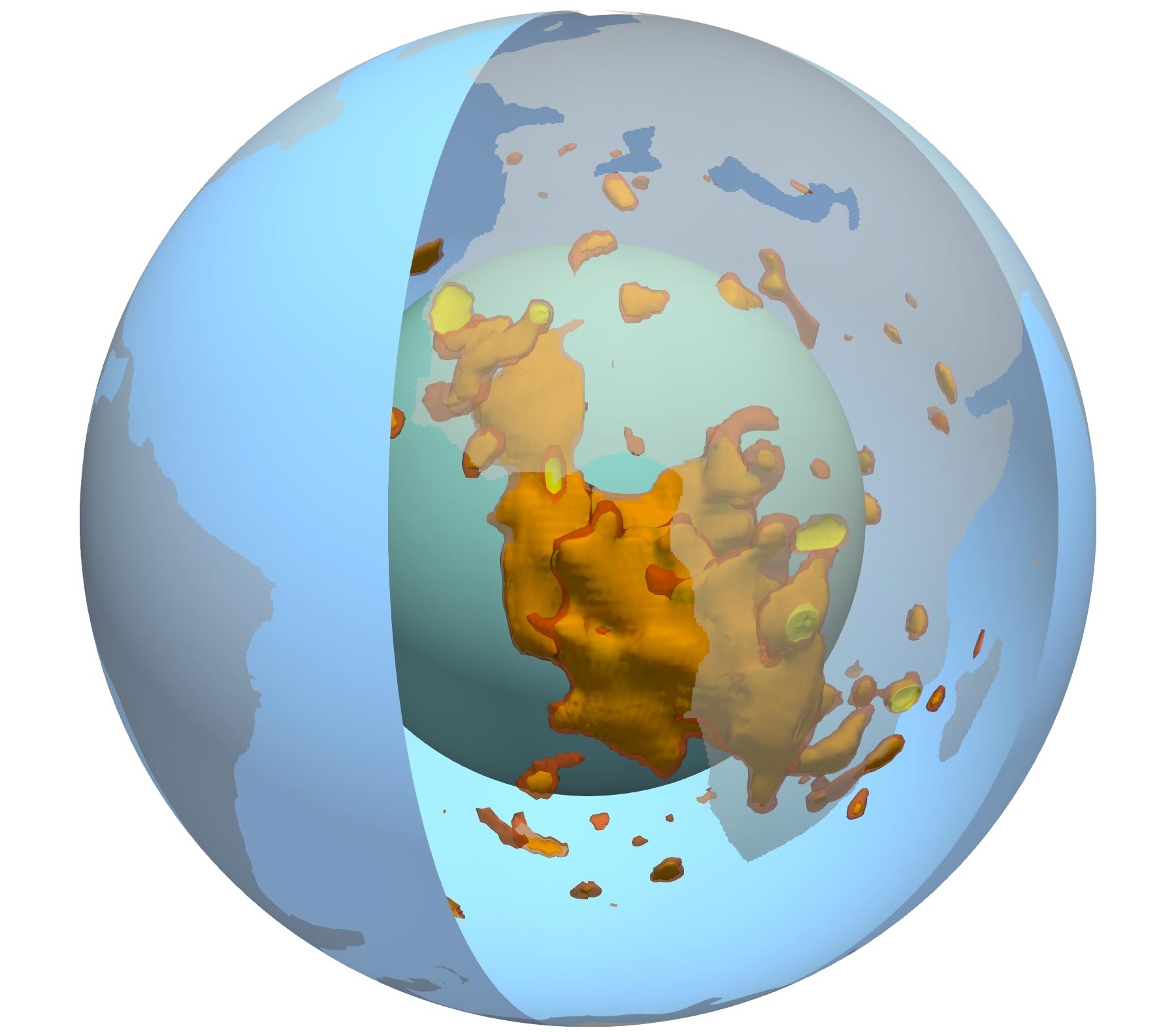

3D-Ansicht des Punktes im Erdmantel unter Afrika, dargestellt in Rot, Gelb und Orange. Cyan stellt die Hauptmantelgrenze dar, Blau zeigt die Oberfläche an und transparentes Grau zeigt die Kontinente an. Bildnachweis: Mingming Li / ASU

Die Erde ist wie eine Zwiebel geschichtet, mit einer dünnen äußeren Kruste, einem dicken, klebrigen Mantel, einem flüssigen äußeren Kern und einem festen inneren Kern. Innerhalb des Mantels gibt es zwei massive punktartige Strukturen, ungefähr auf beiden Seiten des Planeten. Die offiziell als Large Low Speed Provinces (LLSVPs) bezeichneten Punkte sind jeweils so groß wie ein Kontinent und 100-mal höher als der Mount Everest. Einer befindet sich unter dem afrikanischen Kontinent, der andere unter dem Pazifischen Ozean.

Mithilfe von Instrumenten, die seismische Wellen messen, wissen Wissenschaftler, dass diese beiden Blobs komplexe Formen und Strukturen haben, aber trotz ihrer bemerkenswerten Merkmale ist wenig darüber bekannt, warum die Blobs existieren oder was zu ihren seltsamen Formen geführt hat.

Die ASU-Wissenschaftler Qian Yuan und Mingming Li vom College of Earth and Space Exploration wollten mithilfe geodynamischer Modelle und Analysen veröffentlichter seismischer Studien mehr über diese beiden Punkte erfahren. Durch ihre Forschung konnten sie die maximale Höhe bestimmen, die Blobs erreichen, und wie die Größe und Dichte von Blobs sowie die umgebende Viskosität im Mantel ihre Höhe steuern können. Ihre Forschungsergebnisse wurden kürzlich in veröffentlicht

The results of their seismic analysis led to a surprising discovery that the blob under the African continent is about 621 miles (1,000 km) higher than the blob under the Pacific Ocean. According to Yuan and Li, the best explanation for the vast height difference between the two is that the blob under the African continent is less dense (and therefore less stable) than the one under the Pacific Ocean.

To conduct their research, Yuan and Li designed and ran hundreds of mantle convection models simulations. They exhaustively tested the effects of key factors that may affect the height of the blobs, including the volume of the blobs and the contrasts of density and viscosity of the blobs compared with their surroundings. They found that to explain the large differences of height between the two blobs, the one under the African continent must be of a lower density than that of the blob under the Pacific Ocean, indicating that the two may have different composition and evolution.

“Our calculations found that the initial volume of the blobs does not affect their height,” lead author Yuan said. “The height of the blobs is mostly controlled by how dense they are and the viscosity of the surrounding mantle.”

“The Africa LLVP may have been rising in recent geological time,” co-author Li added. “This may explain the elevating surface topography and intense volcanism in eastern Africa.”

These findings may fundamentally change the way scientists think about the deep mantle processes and how they can affect the surface of the Earth. The unstable nature of the blob under the African continent, for example, may be related to continental changes in topography, gravity, surface volcanism and plate motion.

“Our combination of the analysis of seismic results and the geodynamic modeling provides new insights on the nature of the Earth’s largest structures in the deep interior and their interaction with the surrounding mantle,” Yuan said. “This work has far-reaching implications for scientists trying to understand the present-day status and the evolution of the deep mantle structure, and the nature of mantle convection.”

Reference: “Instability of the African large low-shear-wave-velocity province due to its low intrinsic density” by Qian Yuan and Mingming Li, 10 March 2022, Nature Geoscience.

DOI: 10.1038/s41561-022-00908-3

:quality(85)//cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/RMBQWIH4MND6FBJJCRCLGLUSZM.jpg)