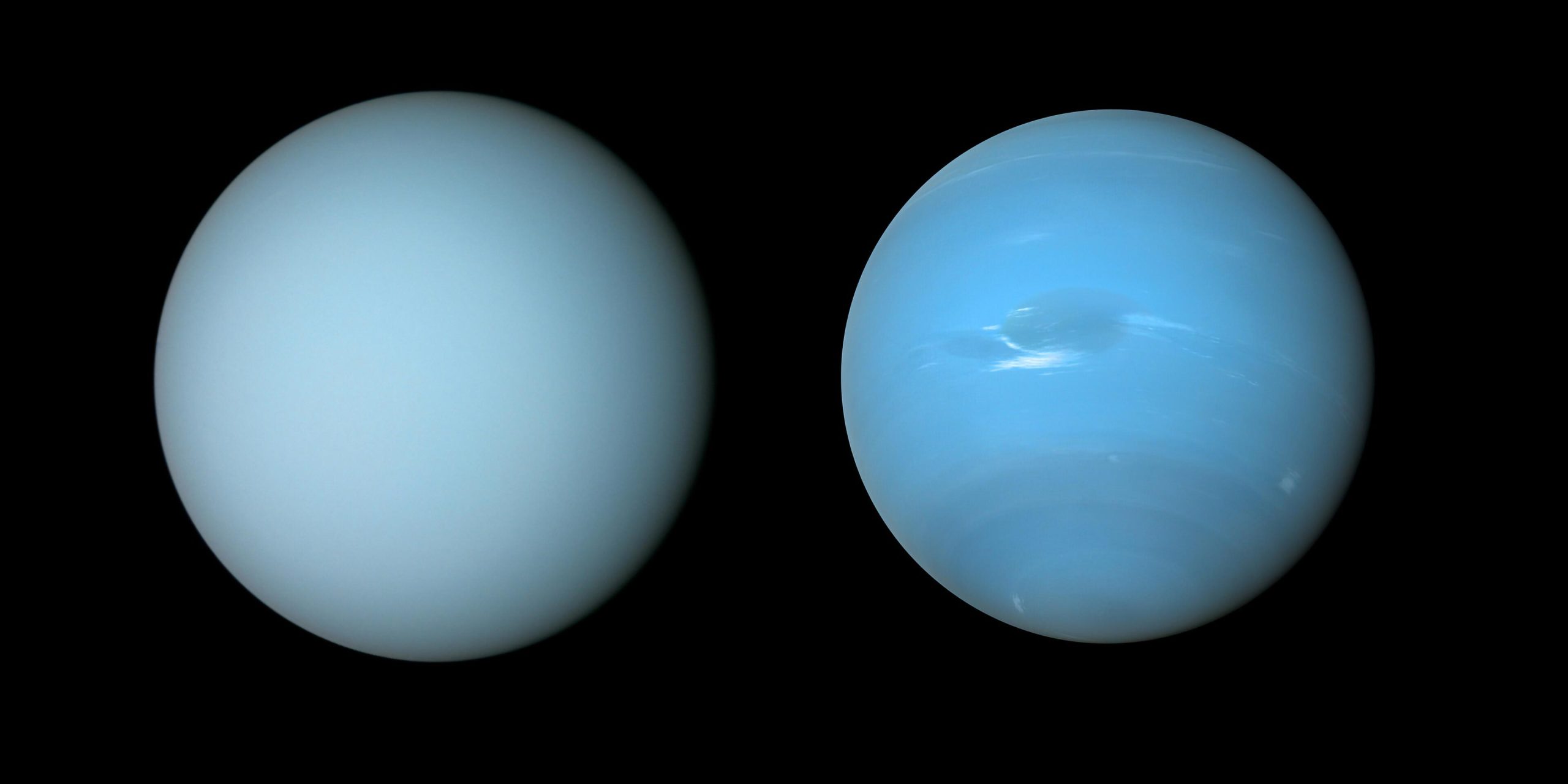

Die NASA-Raumsonde Voyager 2 hat diese Ansichten von Uranus (links) und Neptun (rechts) während Vorbeiflügen an Planeten in den 1980er Jahren aufgenommen. Bildnachweis: NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Johnson

Beobachtungen vom Gemini Observatory und anderen Teleskopen zeigen übermäßigen Dunst[{“ attribute=““>Uranus makes it paler than Neptune.

Astronomers may now understand why the similar planets Uranus and Neptune have distinctive hues. Researchers constructed a single atmospheric model that matches observations of both planets using observations from the Gemini North telescope, the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, and the Hubble Space Telescope. The model reveals that excess haze on Uranus accumulates in the planet’s stagnant, sluggish atmosphere, giving it a lighter hue than Neptune.

Die Planeten Neptun und Uranus haben viel gemeinsam – sie haben ähnliche Massen, Größen und atmosphärische Zusammensetzungen – und doch sind ihre Erscheinungen deutlich unterschiedlich. Bei sichtbaren Wellenlängen hat Neptun eine sichtbar blauere Farbe, während Uranus einen blassen Cyan-Ton hat. Astronomen haben jetzt eine Erklärung dafür, warum die beiden Planeten so unterschiedliche Farben haben.

Neue Forschungsergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass die auf beiden Planeten gefundene Schicht aus konzentriertem Dunst auf Uranus dicker ist als eine ähnliche Schicht auf Neptun und das Erscheinungsbild von Uranus stärker „aufhellt“ als auf Neptun.[1] Wenn kein Nebel drin ist Ambiente Von Neptun und Uranus erscheinen beide ungefähr gleich blau.[2]

Diese Schlussfolgerung kommt von einem Modell[3] die ein internationales Team unter der Leitung von Patrick Irwin, Professor für Planetenphysik an der Universität Oxford, entwickelt hat, um die Aerosolschichten in den Atmosphären von Neptun und Uranus zu beschreiben.[4] Frühere Untersuchungen der oberen Atmosphären dieser Planeten konzentrierten sich nur auf das Erscheinungsbild der Atmosphäre bei bestimmten Wellenlängen. Dieses neue Modell, das aus mehreren atmosphärischen Schichten besteht, stimmt jedoch mit den Beobachtungen beider Planeten über einen weiten Wellenlängenbereich überein. Das neue Modell umfasst auch unscharfe Partikel in tieferen Schichten, von denen man bisher annahm, dass sie nur Wolken aus Methan und Schwefelwasserstoff-Eis enthalten.

Dieses Diagramm zeigt drei Aerosolschichten in den Atmosphären von Uranus und Neptun, wie sie von einem Team von Wissenschaftlern unter der Leitung von Patrick Irwin entworfen wurden. Der Höhenmesser in der Grafik stellt den Druck über 10 bar dar.

Die tiefste Schicht (Aerosolschicht-1) ist dick und besteht aus einer Mischung aus Schwefelwasserstoffeis und Partikeln aus der Wechselwirkung von Planetenatmosphären mit Sonnenlicht.

Die Hauptschicht, die die Farben beeinflusst, ist die mittlere Schicht, eine Schicht aus Nebelpartikeln (in der Veröffentlichung als Aerosolschicht-2 bezeichnet), die auf Uranus dicker ist als auf Neptun. Das Team vermutet, dass auf beiden Planeten Methaneis auf den Partikeln in dieser Schicht kondensiert und die Partikel tiefer in die Atmosphäre zieht, wenn der Methanschnee fällt. Da die Atmosphäre von Neptun aktiver und turbulenter ist als die von Uranus, glaubt das Team, dass die Atmosphäre von Neptun effizienter darin ist, Methanpartikel in die Dunstschicht zu schieben und diesen Schnee zu produzieren. Dies entfernt mehr Dunst und hält Neptuns Dunstschicht dünner als auf Uranus, was bedeutet, dass Neptuns Blau stärker erscheint.

Über beiden Schichten befindet sich eine ausgedehnte Nebelschicht (Aerosolschicht 3), die der darunter liegenden Schicht ähnlich, aber zerbrechlicher ist. Auf Neptun bilden sich auch über dieser Schicht große Methan-Eispartikel.

Bildnachweis: Gemini International Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA, J. da Silva/NASA/JPL-Caltech/B. Johnson

„Dies ist das erste Modell, das Beobachtungen von reflektiertem Sonnenlicht von Ultraviolett bis Nahinfrarot synchron anpasst“, erklärte Irwin, Hauptautor einer Forschungsarbeit, in der dieser Befund im Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets vorgestellt wird. „Er ist auch der Erste, der den Unterschied in der sichtbaren Farbe zwischen Uranus und Neptun erklärt.“

Das Modell des Teams besteht aus drei Aerosolschichten in unterschiedlichen Höhen.[5] Die Hauptschicht, die die Farben beeinflusst, ist die Mittelschicht, eine Schicht aus Nebelpartikeln (in der Veröffentlichung als Aerosolschicht-2 bezeichnet), die über der Schicht dicker ist Uranus Des Neptun. Das Team vermutet, dass auf beiden Planeten Methaneis auf den Partikeln in dieser Schicht kondensiert und die Partikel tiefer in die Atmosphäre zieht, wenn der Methanschnee fällt. Da die Atmosphäre von Neptun aktiver und turbulenter ist als die von Uranus, glaubt das Team, dass die Atmosphäre von Neptun effizienter darin ist, Methanpartikel in die Dunstschicht zu schieben und diesen Schnee zu produzieren. Dies entfernt mehr Dunst und hält Neptuns Dunstschicht dünner als auf Uranus, was bedeutet, dass Neptuns Blau stärker erscheint.

Mike Wong, ein Astronom bei[{“ attribute=““>University of California, Berkeley, and a member of the team behind this result. “Explaining the difference in color between Uranus and Neptune was an unexpected bonus!”

To create this model, Irwin’s team analyzed a set of observations of the planets encompassing ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared wavelengths (from 0.3 to 2.5 micrometers) taken with the Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NIFS) on the Gemini North telescope near the summit of Maunakea in Hawai‘i — which is part of the international Gemini Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab — as well as archival data from the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility, also located in Hawai‘i, and the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope.

The NIFS instrument on Gemini North was particularly important to this result as it is able to provide spectra — measurements of how bright an object is at different wavelengths — for every point in its field of view. This provided the team with detailed measurements of how reflective both planets’ atmospheres are across both the full disk of the planet and across a range of near-infrared wavelengths.

“The Gemini observatories continue to deliver new insights into the nature of our planetary neighbors,” said Martin Still, Gemini Program Officer at the National Science Foundation. “In this experiment, Gemini North provided a component within a suite of ground- and space-based facilities critical to the detection and characterization of atmospheric hazes.”

The model also helps explain the dark spots that are occasionally visible on Neptune and less commonly detected on Uranus. While astronomers were already aware of the presence of dark spots in the atmospheres of both planets, they didn’t know which aerosol layer was causing these dark spots or why the aerosols at those layers were less reflective. The team’s research sheds light on these questions by showing that a darkening of the deepest layer of their model would produce dark spots similar to those seen on Neptune and perhaps Uranus.

Notes

- This whitening effect is similar to how clouds in exoplanet atmospheres dull or ‘flatten’ features in the spectra of exoplanets.

- The red colors of the sunlight scattered from the haze and air molecules are more absorbed by methane molecules in the atmosphere of the planets. This process — referred to as Rayleigh scattering — is what makes skies blue here on Earth (though in Earth’s atmosphere sunlight is mostly scattered by nitrogen molecules rather than hydrogen molecules). Rayleigh scattering occurs predominantly at shorter, bluer wavelengths.

- An aerosol is a suspension of fine droplets or particles in a gas. Common examples on Earth include mist, soot, smoke, and fog. On Neptune and Uranus, particles produced by sunlight interacting with elements in the atmosphere (photochemical reactions) are responsible for aerosol hazes in these planets’ atmospheres.

- A scientific model is a computational tool used by scientists to test predictions about a phenomena that would be impossible to do in the real world.

- The deepest layer (referred to in the paper as the Aerosol-1 layer) is thick and is composed of a mixture of hydrogen sulfide ice and particles produced by the interaction of the planets’ atmospheres with sunlight. The top layer is an extended layer of haze (the Aerosol-3 layer) similar to the middle layer but more tenuous. On Neptune, large methane ice particles also form above this layer.

More information

This research was presented in the paper “Hazy blue worlds: A holistic aerosol model for Uranus and Neptune, including Dark Spots” to appear in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.

The team is composed of P.G.J. Irwin (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), N.A. Teanby (School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, UK), L.N. Fletcher (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), D. Toledo (Instituto Nacional de Tecnica Aeroespacial, Spain), G.S. Orton (Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, USA), M.H. Wong (Center for Integrative Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, USA), M.T. Roman (School of Physics & Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK), S. Perez-Hoyos (University of the Basque Country, Spain), A. James (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK), J. Dobinson (Department of Physics, University of Oxford, UK).

NSF’s NOIRLab (National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory), the US center for ground-based optical-infrared astronomy, operates the international Gemini Observatory (a facility of NSF, NRC–Canada, ANID–Chile, MCTIC–Brazil, MINCyT–Argentina, and KASI–Republic of Korea), Kitt Peak National Observatory (KPNO), Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO), the Community Science and Data Center (CSDC), and Vera C. Rubin Observatory (operated in cooperation with the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory). It is managed by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with NSF and is headquartered in Tucson, Arizona. The astronomical community is honored to have the opportunity to conduct astronomical research on Iolkam Du’ag (Kitt Peak) in Arizona, on Maunakea in Hawai‘i, and on Cerro Tololo and Cerro Pachón in Chile. We recognize and acknowledge the very significant cultural role and reverence that these sites have for the Tohono O’odham Nation, the Native Hawaiian community, and the local communities in Chile, respectively.