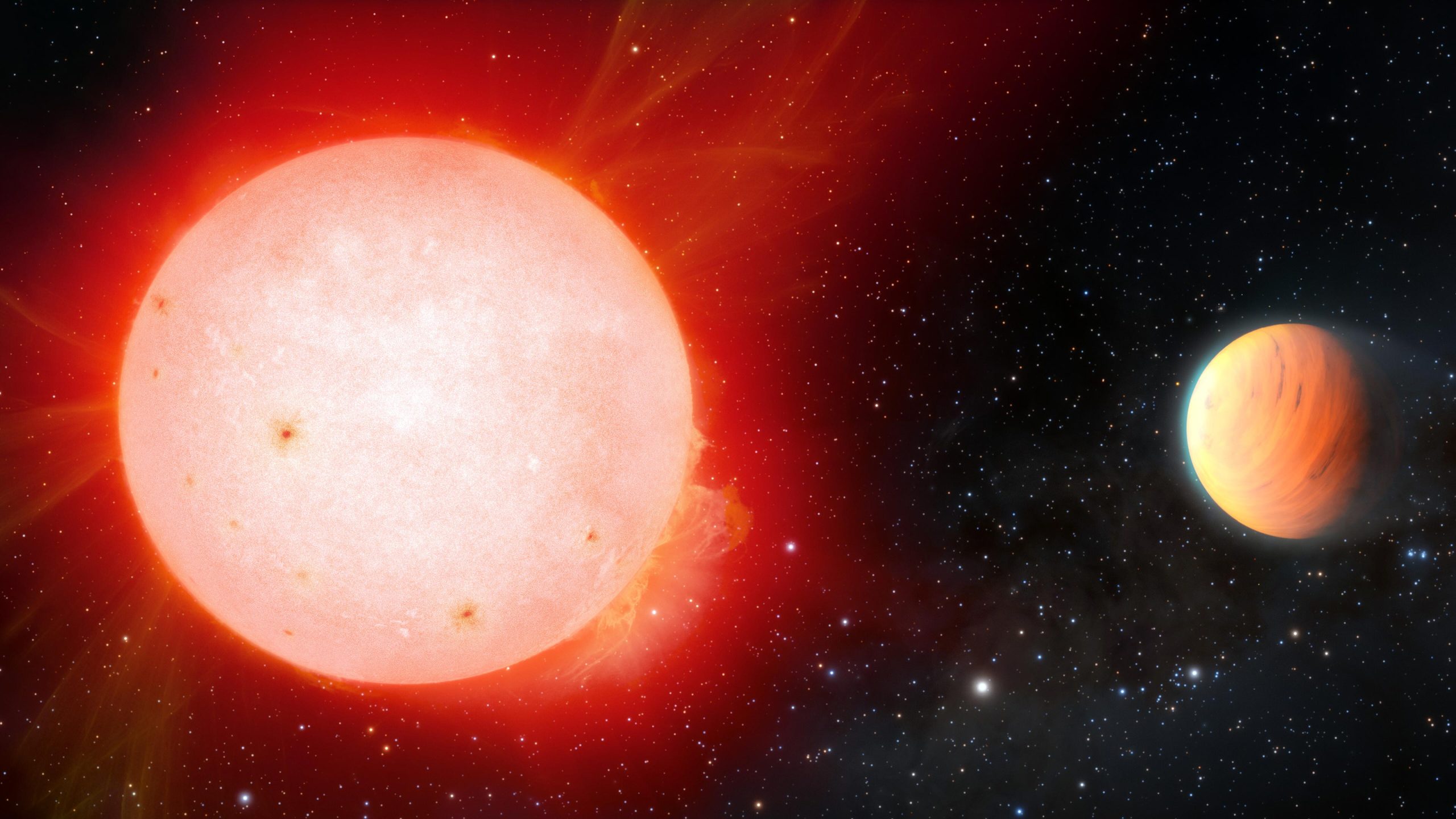

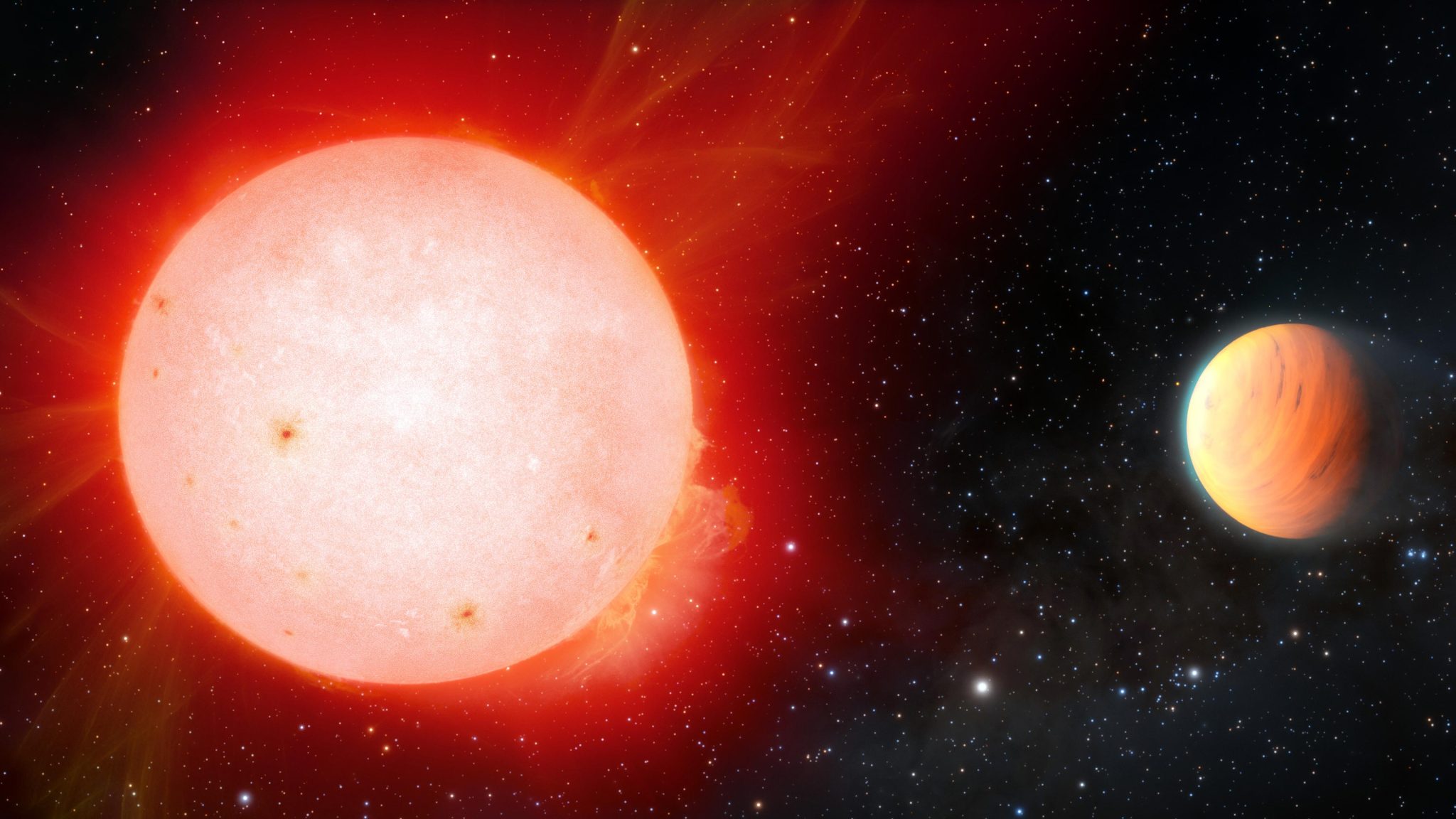

Künstlerische Darstellung eines sehr dünnen Gasriesenplaneten, der einen roten Zwergstern umkreist. Äußerer Gasriese [right] Dichte von Marshmallows im Orbit um einen kühlen roten Zwergstern entdeckt [left] vom NASA-finanzierten NEID Radial Velocity Instrument am 3,5-Meter-WIYN-Teleskop am Kitt Peak National Observatory, einem Programm des NSF NOIRLab. Der Planet mit der Bezeichnung TOI-3757 b ist der dünnste Gasriesenplanet, der je um diesen Sterntyp herum entdeckt wurde. Bildnachweis: NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/J. da Silva/Spaceengine/M. Zamani

Das Kitt Peak Telescope des National Observatory hilft bei der Bestimmung[{“ attribute=““>Jupiter-like Planet is the lowest-density gas giant ever detected around a red dwarf.

A gas giant exoplanet with the density of a marshmallow has been detected in orbit around a cool red dwarf star. A suite of astronomical instruments was used to make the observations, including the NASA-funded NEID radial-velocity instrument on the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, a Program of NSF’s NOIRLab. Named TOI-3757 b, the exoplanet is the fluffiest gas giant planet ever discovered around this type of star.

Using the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona, astronomers have observed an unusual Jupiter-like planet in orbit around a cool red dwarf star. Located in the constellation of Auriga the Charioteer around 580 light-years from Earth, this planet, identified as TOI-3757 b, is the lowest-density planet ever detected around a red dwarf star and is estimated to have an average density akin to that of a marshmallow.

Red dwarf stars are the smallest and dimmest members of so-called main-sequence stars — stars that convert hydrogen into helium in their cores at a steady rate. Although they are “cool” compared to stars like our Sun, red dwarf stars can be extremely active and erupt with powerful flares. This can strip orbiting planets of their atmospheres, making this star system a seemingly inhospitable location to form such a gossamer planet.

Shubham Kanodia, Forscher am Earth and Planetary Laboratory der Carnegie Institution for Science und Erstautor eines in Astrologische Zeitschriftzu. Bisher wurde dies nur von kleinen Stichproben von Doppler-Durchmusterungen gesehen, die normalerweise Riesenplaneten weit entfernt von diesen roten Zwergsternen gefunden haben. Bis jetzt hatten wir keine ausreichend große Stichprobe von Planeten, um nahe gelegene Gasplaneten zuverlässig zu finden.“

Es gibt immer noch ungeklärte Geheimnisse rund um TOI-3757 b, darunter vor allem, wie sich ein Gasriesenplanet um einen roten Zwergstern bilden konnte, insbesondere ein Planet mit geringer Dichte. Das Kanodia-Team glaubt jedoch, dass es eine Lösung für dieses Rätsel gefunden hat.

Vom Gelände des Kit Peak National Observatory (KPNO), einem Programm des NSF NOIRLab, scheint das 3,5-Meter-Teleskop Wisconsin-Indiana-Yale-NOIRLab (WIYN) die Milchstraße zu beobachten, wie sie aus dem Horizont heraustritt. Auch rötlicher atmosphärischer Glanz, ein Naturphänomen, färbt den Horizont. KPNO befindet sich in der Sonora-Wüste von Arizona in der Tohono O’odham Nation, und diese klare Ansicht eines Teils der Ebene der Milchstraße zeigt die günstigen Bedingungen in dieser Umgebung, die erforderlich sind, um schwache Himmelskörper zu sehen. Diese Bedingungen, zu denen geringe Lichtverschmutzung, 20° dunklerer Himmel und trockene atmosphärische Bedingungen gehören, ermöglichten es den Forschern des WIYN-Konsortiums, Beobachtungen von Galaxien, Nebeln und Exoplaneten sowie vielen anderen astronomischen Zielen mit dem WIYN 3,5-Meter zu verfolgen Teleskop und sein Schwesterteleskop WIYN 0,9-Meter-Teleskop. Bildnachweis: KPNO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R.Sparks

Sie schlagen vor, dass die extrem niedrige Dichte von TOI-3757 b das Ergebnis von zwei Faktoren sein könnte. Der erste bezieht sich auf den felsigen Kern des Planeten; Es wird angenommen, dass Gasriesen als massive felsige Kerne mit einer Masse von etwa der zehnfachen Masse der Erde beginnen, an welcher Stelle sie schnell große Mengen nahe gelegenen Gases ansaugen, um die Gasriesen zu bilden, die wir heute sehen. TOI-3757b hat eine geringere Häufigkeit schwerer Elemente als andere M-Zwerge mit Gasriesen, und dies könnte dazu geführt haben, dass sich der felsige Kern langsamer gebildet hat, was den Beginn der Gasansammlung verzögert und somit die Gesamtdichte des Planeten beeinflusst.

Ein zweiter Faktor könnte die Umlaufbahn des Planeten sein, von der vorläufig angenommen wird, dass sie leicht elliptisch ist. Es gibt Zeiten, in denen es seinem Stern näher kommt als zu anderen Zeiten, was zu einer erheblichen Überhitzung führt, die dazu führen kann, dass die Atmosphäre des Planeten anschwillt.

Transitsatellit der NASA für Exoplaneten-Durchmusterung ([{“ attribute=““>TESS) initially spotted the planet. Kanodia’s team then made follow-up observations using ground-based instruments, including NEID and NESSI (NN-EXPLORE Exoplanet Stellar Speckle Imager), both housed at the WIYN 3.5-meter Telescope; the Habitable-zone Planet Finder (HPF) on the Hobby-Eberly Telescope; and the Red Buttes Observatory (RBO) in Wyoming.

TESS surveyed the crossing of this planet TOI-3757 b in front of its star, which allowed astronomers to calculate the planet’s diameter to be about 150,000 kilometers (100,000 miles) or about just slightly larger than that of Jupiter. The planet finishes one complete orbit around its host star in just 3.5 days, 25 times less than the closest planet in our Solar System — Mercury — which takes about 88 days to do so.

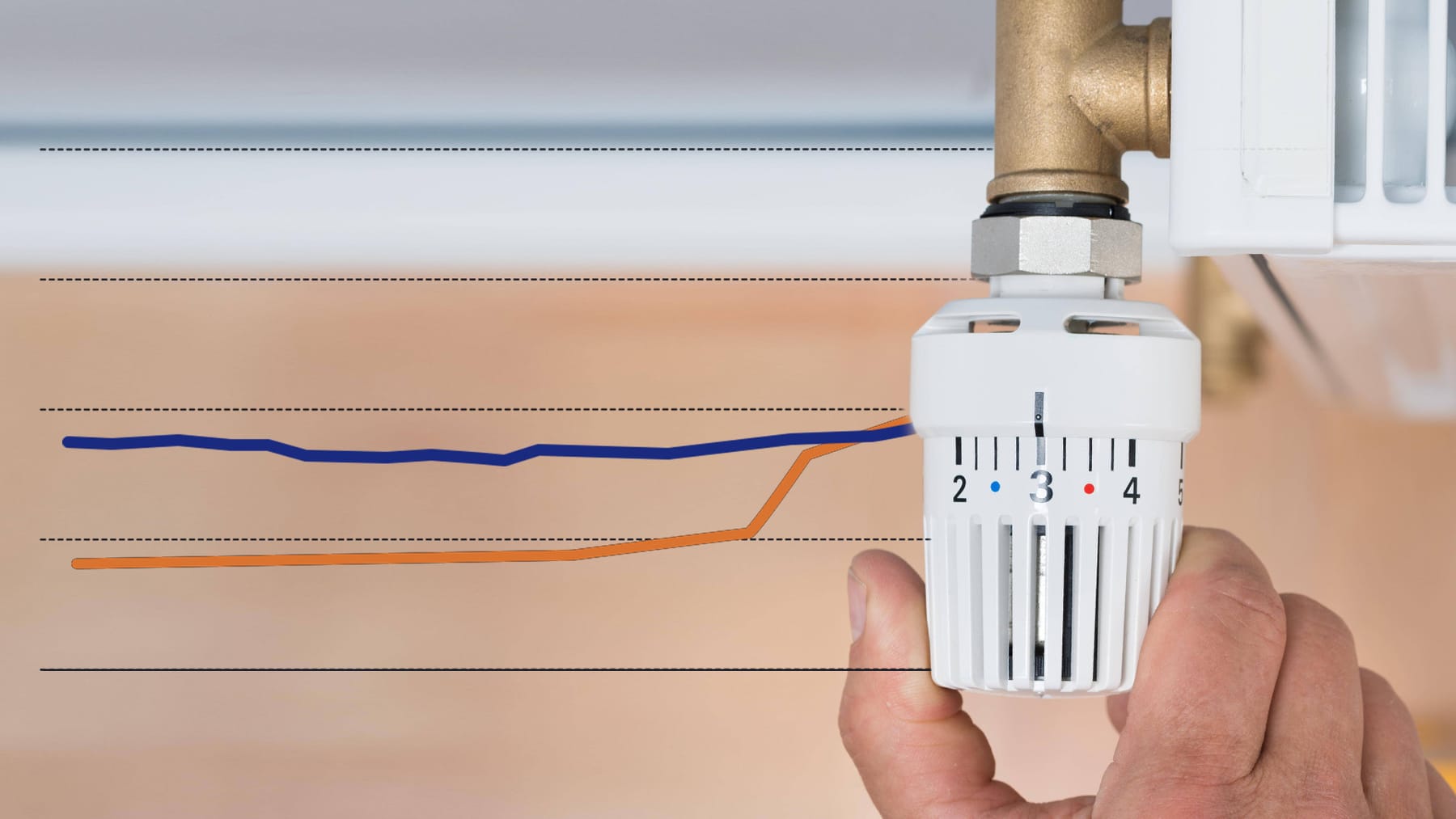

The astronomers then used NEID and HPF to measure the star’s apparent motion along the line of sight, also known as its radial velocity. These measurements provided the planet’s mass, which was calculated to be about one-quarter that of Jupiter, or about 85 times the mass of the Earth. Knowing the size and the mass allowed Kanodia’s team to calculate TOI-3757 b’s average density as being 0.27 grams per cubic centimeter (about 17 grams per cubic feet), which would make it less than half the density of Saturn (the lowest-density planet in the Solar System), about one quarter the density of water (meaning it would float if placed in a giant bathtub filled with water), or in fact, similar in density to a marshmallow.

“Potential future observations of the atmosphere of this planet using NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope could help shed light on its puffy nature,” says Jessica Libby-Roberts, a postdoctoral researcher at Pennsylvania State University and the second author on this paper.

“Finding more such systems with giant planets — which were once theorized to be extremely rare around red dwarfs — is part of our goal to understand how planets form,” says Kanodia.

The discovery highlights the importance of NEID in its ability to confirm some of the candidate exoplanets currently being discovered by NASA’s TESS mission, providing important targets for the new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to follow up on and begin characterizing their atmospheres. This will in turn inform astronomers what the planets are made of and how they formed and, for potentially habitable rocky worlds, whether they might be able to support life.

Reference: “TOI-3757 b: A low-density gas giant orbiting a solar-metallicity M dwarf” by Shubham Kanodia, Jessica Libby-Roberts, Caleb I. Cañas, Joe P. Ninan, Suvrath Mahadevan, Gudmundur Stefansson, Andrea S. J. Lin, Sinclaire Jones, Andrew Monson, Brock A. Parker, Henry A. Kobulnicky, Tera N. Swaby, Luke Powers, Corey Beard, Chad F. Bender, Cullen H. Blake, William D. Cochran, Jiayin Dong, Scott A. Diddams, Connor Fredrick, Arvind F. Gupta, Samuel Halverson, Fred Hearty, Sarah E. Logsdon, Andrew J. Metcalf, Michael W. McElwain, Caroline Morley, Jayadev Rajagopal, Lawrence W. Ramsey, Paul Robertson, Arpita Roy, Christian Schwab, Ryan C. Terrien, John Wisniewski and Jason T. Wright, 5 August 2022, The Astronomical Journal.

DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ac7c20