Kleiner Clip zur Simulation von Thesan. Sehen Sie sich das Video im folgenden Artikel an.

Benannt nach der Göttin der Morgendämmerung, helfen Thesans Simulationen der ersten Milliarde Jahre zu erklären, wie Strahlung das frühe Universum geformt hat.

Alles begann vor etwa 13,8 Milliarden Jahren mit dem großen kosmischen „Knall“, der plötzlich und auf erstaunliche Weise das Universum erschuf. Bald kühlte das junge Universum dramatisch ab und wurde vollständig dunkel.

Dann, innerhalb von ein paar hundert Millionen Jahren danach[{“ attribute=““>Big Bang, the universe woke up, as gravity gathered matter into the first stars and galaxies. Light from these first stars turned the surrounding gas into a hot, ionized plasma — a crucial transformation known as cosmic reionization that propelled the universe into the complex structure that we see today.

Now, scientists can get a detailed view of how the universe may have unfolded during this pivotal period with a new simulation, known as Thesan, developed by scientists at MIT, Harvard University, and the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics.

Named after the Etruscan goddess of the dawn, Thesan is designed to simulate the “cosmic dawn,” and specifically cosmic reionization, a period which has been challenging to reconstruct, as it involves immensely complicated, chaotic interactions, including those between gravity, gas, and radiation.

The Thesan simulation resolves these interactions with the highest detail and over the largest volume of any previous simulation. It does so by combining a realistic model of galaxy formation with a new algorithm that tracks how light interacts with gas, along with a model for cosmic dust.

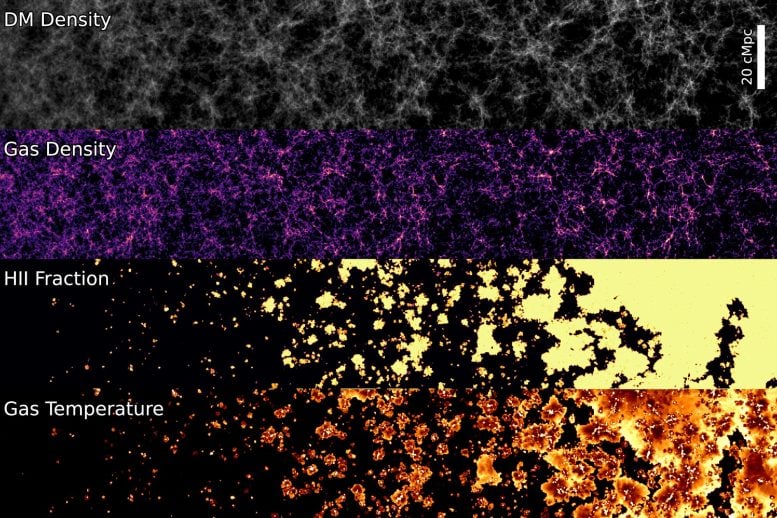

Evolution of simulated properties in the main Thesan run. Time progresses from left to right. The dark matter (top panel) collapse in the cosmic web structure, composed of clumps (haloes) connected by filaments, and the gas (second panel from the top) follows, collapsing to create galaxies. These produce ionizing photons that drive cosmic reionization (third panel from the top), heating up the gas in the process (bottom panel). Credit: Courtesy of THESAN Simulations

With Thesan, the researchers can simulate a cubic volume of the universe spanning 300 million light years across. They run the simulation forward in time to track the first appearance and evolution of hundreds of thousands of galaxies within this space, beginning around 400,000 years after the Big Bang, and through the first billion years.

So far, the simulations align with what few observations astronomers have of the early universe. As more observations are made of this period, for instance with the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope, Thesan may help to place such observations in cosmic context.

For now, the simulations are starting to shed light on certain processes, such as how far light can travel in the early universe, and which galaxies were responsible for reionization.

“Thesan acts as a bridge to the early universe,” says Aaron Smith, a NASA Einstein Fellow in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “It is intended to serve as an ideal simulation counterpart for upcoming observational facilities, which are poised to fundamentally alter our understanding of the cosmos.”

Smith and Mark Vogelsberger, associate professor of physics at MIT, Rahul Kannan of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and Enrico Garaldi at Max Planck have introduced the Thesan simulation through three papers, the third published on March 24, 2022, in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow the light

In the earliest stages of cosmic reionization, the universe was a dark and homogenous space. For physicists, the cosmic evolution during these early “dark ages” is relatively simple to calculate.

“In principle you could work this out with pen and paper,” Smith says. “But at some point gravity starts to pull and collapse matter together, at first slowly, but then so quickly that calculations become too complicated, and we have to do a full simulation.”

To fully simulate cosmic reionization, the team sought to include as many major ingredients of the early universe as possible. They started off with a successful model of galaxy formation that their groups previously developed, called Illustris-TNG, which has been shown to accurately simulate the properties and populations of evolving galaxies. They then developed a new code to incorporate how the light from galaxies and stars interact with and reionize the surrounding gas — an extremely complex process that other simulations have not been able to accurately reproduce at large scale.

“Thesan follows how the light from these first galaxies interacts with the gas over the first billion years and transforms the universe from neutral to ionized,” Kannan says. “This way, we automatically follow the reionization process as it unfolds.”

Finally, the team included a preliminary model of cosmic dust — another feature that is unique to such simulations of the early universe. This early model aims to describe how tiny grains of material influence the formation of galaxies in the early, sparse universe.

Diese Simulation von Gasentwicklung und Strahlung zeigt eine Ausführungsform von neutralem Wasserstoffgas. Die Farben stehen für Intensität und Helligkeit und offenbaren die unvollständige Reionisationsstruktur innerhalb eines Netzwerks hochdichter neutraler Gasfäden.

kosmische Brücke

Mit den vorhandenen Simulationskomponenten bestimmte das Team seine Anfangsbedingungen für etwa 400.000 Jahre nach dem Urknall, basierend auf präzisen Messungen des Restlichts des Urknalls. Anschließend entwickelten sie diese Bedingungen rechtzeitig weiter, um einen Teil des Universums zu simulieren, indem sie die SuperMUC-NG-Maschine – einen der größten Supercomputer der Welt – verwendeten, die gleichzeitig 60.000 Computerkerne nutzte, um Thesan-Berechnungen auf dem Äquivalent von 30 Millionen CPUs durchzuführen. eine Stunde (ein Aufwand, der 3.500 Jahre gedauert hätte, um auf einem einzigen Desktop ausgeführt zu werden).

Die Simulationen lieferten die detaillierteste Ansicht der kosmischen Reionisation über das größte Raumvolumen aller existierenden Simulationen. Während einige Simulationen über große Entfernungen laufen, tun sie dies mit einer relativ niedrigen Auflösung, während andere, detailliertere Simulationen keine großen Größen umfassen.

„Wir pendeln zwischen diesen beiden Ansätzen: Wir haben hohes Volumen und hohe Präzision“, betont Vogelsberger.

Frühe Analysen der Simulationen deuten darauf hin, dass am Ende der kosmischen Reionisation die Entfernung, die das Licht zurücklegen kann, deutlich stärker gewachsen ist, als Wissenschaftler bisher angenommen hatten.

„Thesan fand heraus, dass Licht im frühen Universum keine großen Entfernungen zurücklegt“, sagt Canan. „Tatsächlich ist dieser Abstand sehr klein und wird erst am Ende der Reionisierung groß und vergrößert sich in nur wenigen hundert Millionen Jahren um das Zehnfache.“

Forscher sehen auch Hinweise auf die Art von Galaxien, die für die Reionisierung verantwortlich sind. Die Masse der Galaxie scheint die Reionisierung zu beeinflussen, obwohl das Team sagt, dass weitere Beobachtungen von James Webb und anderen Observatorien helfen werden, diese dominanten Galaxien zu identifizieren.

„Da sind viele bewegliche Teile drin [modeling cosmic reionization]“, schließt Vogelsberger. „Wenn wir all dies in einer Art Maschine zusammenfügen und anfangen können, sie zu betreiben und zu einem dynamischen Universum zu führen, ist das für uns alle ein sehr lohnender Moment.“

Referenz: „This Project: Lyman-A Emission and Transfer during the Reionization Era“ von A. Smith, R. Cannan, E. Garaldi, M. Vogelsberger, R. Buckmore, in Sprinkle und L. Hernquist, 24. März 2022 Hier verfügbar Monatliche Mitteilungen der Royal Astronomical Society.

DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stac713

Diese Forschung wurde teilweise von der NASA, der National Science Foundation und dem Gauss Center for Supercomputing unterstützt.