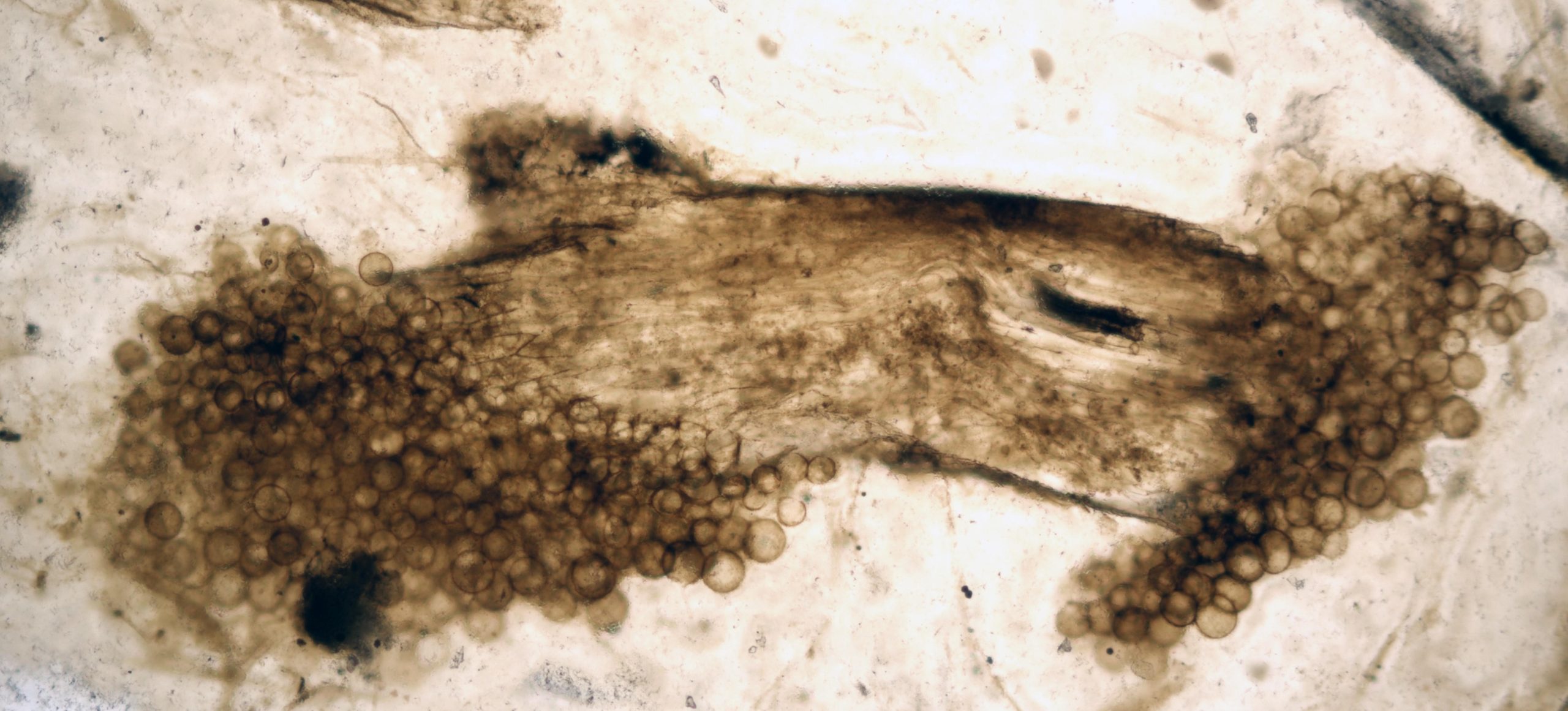

Ein kleines Stück einer fossilen Rheinpflanze mit fossilen Pilzen, die die Gliedmaßen besiedeln, durch ein Mikroskop gesehen. Bildnachweis: Loron et al.

Modernste Technologie hat neue Einblicke in einen weltberühmten Fossilienschatz gebracht, der wichtige Hinweise auf das frühe Leben auf der Erde liefern könnte.

Wissenschaftler, die den 400 Millionen Jahre alten Fossilien-Cache untersuchen, der in der abgelegenen nordöstlichen Region Schottlands ausgegraben wurde, berichten, dass ihre Ergebnisse einen höheren Grad der molekularen Erhaltung in diesen Fossilien zeigen als bisher erwartet.

Eine neue Untersuchung der hervorragend erhaltenen Schatzkammer aus Aberdeenshire hat es Wissenschaftlern ermöglicht, die chemischen Fingerabdrücke der verschiedenen darin enthaltenen Organismen zu identifizieren.

So wie der Rosetta-Stein Ägyptologen bei der Übersetzung von Hieroglyphen half, hofft das Team, dass diese alchemistischen Symbole dazu beitragen werden, mehr über die Identität von Lebensformen zu verstehen, die durch andere, unbekanntere Fossilien dargestellt werden.

Das atemberaubende fossile Ökosystem wurde 1912 in der Nähe des Dorfes Rhynie in Aberdeenshire entdeckt und ist mineralisiert und mit hartem Gestein aus Kieselsäure überzogen. Der als Rhynie-Hornstein bekannte Stein stammt aus der frühen Devon-Zeit – vor etwa 407 Millionen Jahren – und spielt eine wichtige Rolle für das Verständnis der Wissenschaftler über das Leben auf der Erde.

Die Forscher kombinierten die neuesten Erkenntnisse der zerstörungsfreien Bildgebung, Datenanalyse und[{“ attribute=““>machine learning to analyze fossils from collections held by National Museums Scotland and the Universities of Aberdeen and Oxford. Scientists from the University of Edinburgh were able to probe deeper than has previously been possible, which they say could reveal new insights about less well-preserved samples.

Employing a technique known as FTIR spectroscopy – in which infrared light is used to collect high-resolution data – researchers found impressive preservation of molecular information within the cells, tissues, and organisms in the rock.

Since they already knew which organisms most of the fossils represented, the team was able to discover molecular fingerprints that reliably discriminate between fungi, bacteria, and other groups.

These fingerprints were then used to identify some of the more mysterious members of the Rhynie ecosystem, including two specimens of an enigmatic tubular “nematophyte”.

These strange organisms, which are found in Devonian – and later Silurian – sediments have both algal and fungal characteristics and were previously hard to place in either category. The new findings indicate that they were unlikely to have been either lichens or fungi.

Dr. Sean McMahon, Chancellor’s Fellow from the University of Edinburgh’s School of Physics and Astronomy and School of GeoSciences, said: “We have shown how a quick, non-invasive method can be used to discriminate between different lifeforms, and this opens a unique window on the diversity of early life on Earth.”

The team fed their data into a machine learning algorithm that was able to classify the different organisms, providing the potential for sorting other datasets from other fossil-bearing rocks.

The study, published in Nature Communications, was funded by The Royal Society, Wallonia–Brussels International, and the National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico.

Dr Corentin Loron, Royal Society Newton International Fellow from the University of Edinburgh’s School of Physics and Astronomy said the study shows the value of bridging paleontology with physics and chemistry to create new insights into early life.

“Our work highlights the unique scientific importance of some of Scotland’s spectacular natural heritage and provides us with a tool for studying life in trickier, more ambiguous remnants,” Dr. Loron said.

Dr. Nick Fraser, Keeper of Natural Sciences at National Museums Scotland, believes the value of museum collections for understanding our world should never be underestimated.

He said: “The continued development of analytical techniques provides new avenues to explore the past. Our new study provides one more way of peering ever deeper into the fossil record.”

Reference: “Molecular fingerprints resolve affinities of Rhynie chert organic fossils” by C. C. Loron, E. Rodriguez Dzul, P. J. Orr, A. V. Gromov, N. C. Fraser and S. McMahon, 13 March 2023, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-023-37047-1